By Maisie Bache-Jeffreys

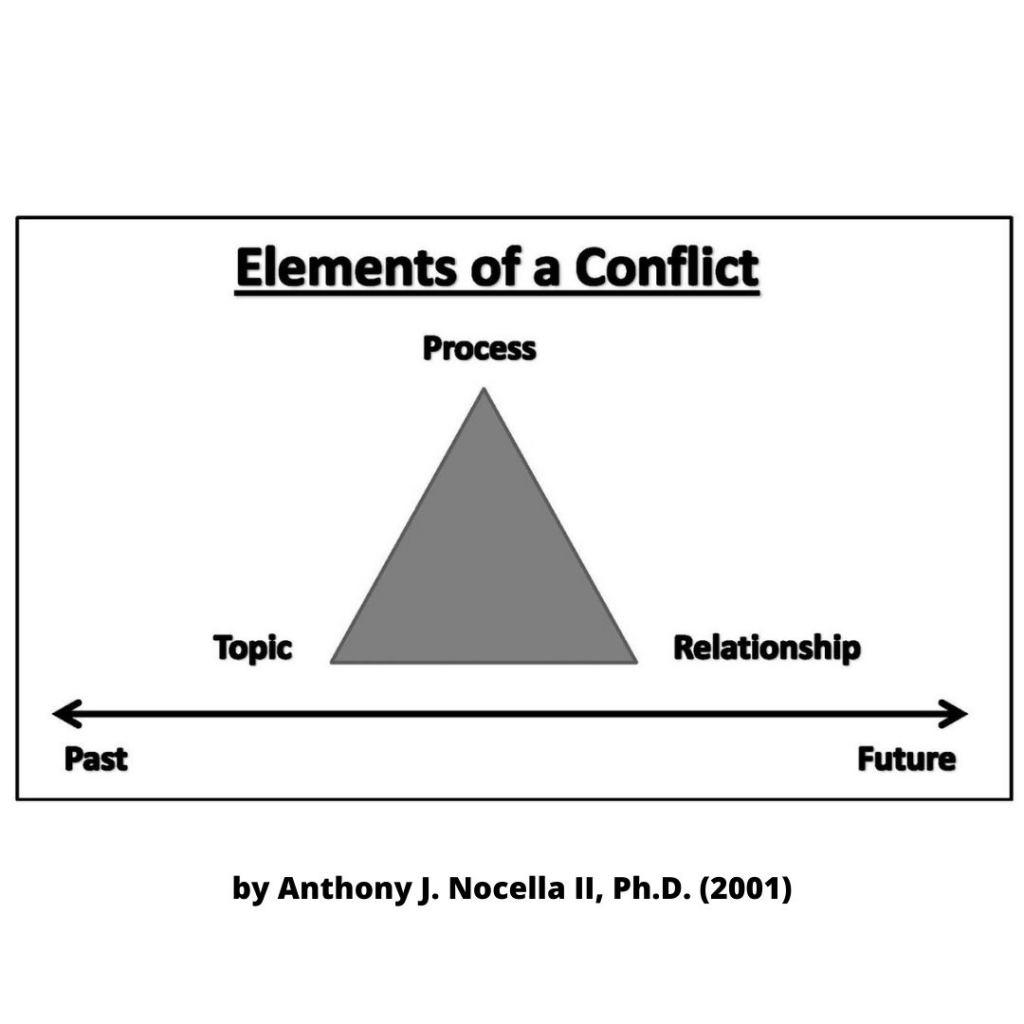

Conflict is rarely the result of a single cause or actor. Whether it’s intercommunal violence, political unrest, or long-term social tension, conflict tends to emerge from a web of interconnected factors – historical tensions, economic exclusion, identity politics, institutional failure, environmental degradation, and more.

Yet too often, our responses remain fragmented. We intervene with narrowly focused programmes – training for youth here, peace messaging there, a dialogue session when tensions flare – without fully understanding the system that generates and sustains the conflict itself.

This is where systems thinking has the potential to shift our perspective and our impact.

Moving Beyond Symptoms

A systems lens asks us to look beyond immediate symptoms and explore underlying structures and patterns. Rather than asking “Who’s to blame?” or “What’s the trigger?”, we ask:

- What feedback loops are reinforcing this conflict?

- What power dynamics or narratives are holding it in place?

- Where are the hidden leverage points for transformation?

Take, for example, a conflict between two communities over land use. On the surface, it may appear as a dispute over territory. But zooming out, we may find decades of unequal land policy, extractive natural resource agreements, political marginalisation, climate-induced displacement, and misinformation – all interacting in ways that fuel mistrust and competition.

Without recognising these interdependencies, we risk designing responses that treat symptoms but leave the deeper system untouched.

Seeing Conflict as a System

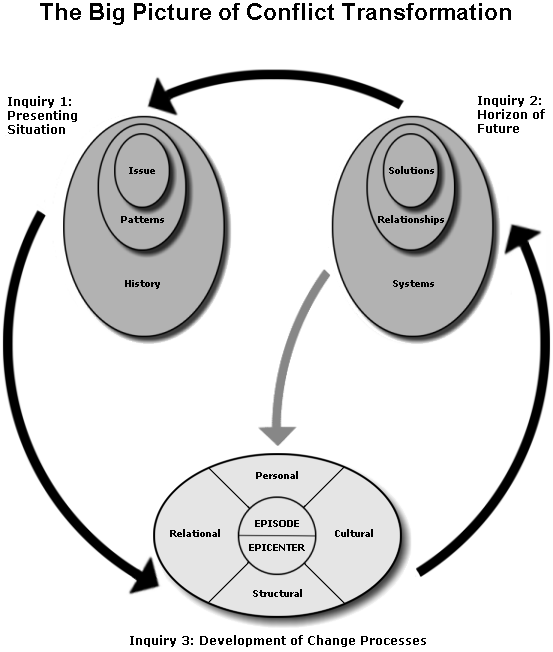

Systems thinking reframes conflict not as a chaotic breakdown, but as an expression of how a system is currently functioning – even if that function is harmful. In this view, conflict is a signal of stress, imbalance, or unaddressed tension within the wider environment.

By mapping the system, we can better understand:

- The actors and institutions involved, both formal and informal

- The relationships between them: cooperative, competitive, exploitative

- The mental models: beliefs, fears and assumptions that shape decisions

- The reinforcing cycles: violence leading to trauma, trauma leading to mistrust, mistrust leading to more violence

This doesn’t make conflict simpler, but it can help make it more comprehensible and aid transformation.

source: https://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/transformation

From Control to Influence

Traditional conflict interventions often seek control: to stabilise, de-escalate, resolve. But complex systems, or even the temporary chaotic system of conflict, often don’t respond well to control – they respond to influence.

A systems approach helps us identify where a small, strategic shift might lead to larger systemic change, what we know as “leverage points.” This might mean shifting a harmful narrative, empowering a credible but under-supported local actor, or changing how a peacebuilding programme collects and responds to community feedback.

It also requires humility. Systems are dynamic. No single actor can transform them alone. This invites a mindset of collaboration, experimentation, and learning.

Listening to Lived Experience

Understanding conflict through a systems lens means elevating local knowledge and lived experience. People closest to the conflict often understand the system best – they navigate its rules, navigate its risks, and see the fault lines that outsiders can miss.

Co-creating systems maps with communities, using storytelling to capture complexity, and recognising traditional conflict resolution systems are all ways to democratise systems thinking, and challenge the assumption that complexity analysis must come from international experts.

This also aligns with decolonising approaches to peacebuilding – where local actors are not just implementers, but analysts, designers, and decision-makers.

A Caveat

We talk about taking a systems-lens to understand conflict, and working with those with lived experience to design interventions that could create small shifts in the system. However, this can be very difficult during active conflict, which can be categorised as a ‘chaotic system’ – often unpredictable, unstable, and highly reactive.

In such contexts, cause and effect break down. Information may be unreliable, power shifts rapidly, and actions that normally build trust may backfire. The urgency of violence often demands immediate response, leaving little space for reflection, participation, or systems mapping, rather than enabling the slower pace of innovation and understanding long-term impacts.

But even in chaos, systems thinking can still guide our approach. Not by trying to impose order, but by helping us sense patterns, identify what stabilises or destabilises a situation, and act with agility. It encourages us to work with frontline actors who have deep contextual intelligence, to prioritise relationships over rigid plans, and to prepare for learning and adaptation over time.

In other words, systems thinking doesn’t require certainty – it requires attentiveness. And in moments of chaos, it may be less about designing perfect interventions and more about creating the conditions for resilience, dialogue, and eventually, transformation.

Conclusion

Understanding conflict through a systems lens doesn’t give us quick answers, and has its challenges, but it gives us better questions. It challenges us to think deeper, act more strategically, and listen more carefully. In doing so, it can move us closer to the kind of change that lasts.

Because conflict isn’t just what’s visible – it’s the system underneath. And to transform it, we need to see the whole picture.