By Maisie Jeffreys

What is systems thinking? Why does it matter? How do we make it less theoretical?

You’re in the right place. We’ve all had it – when looking at frameworks, toolkits, or even hearing the word ‘systems’ itself – feeling lost and asking ourselves “but how does this actually apply to my work?”

The Basics

What do we mean by ‘the system’?

“a system is a set of things – people, cells, molecules or whatever – interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behaviour over time.” – Donella Meadows

“a system contains a number of component parts that are connected in ways we can’t fully know and interact in ways that likely to produce outcomes we can’t fully predict” – Cynefin

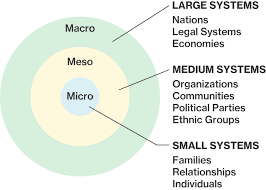

We can break down systems to understand them in many different ways. A common one is:

- Micro level: Individual and family, local community

- Meso level: Institutions / organisations

- Macro level: Wider society and culture

Different types of systems

1. Ordered Systems

These are predictable and controlled

- The rules are clear

- Cause and effect are easy to see

- Example: A car engine or a recipe – if you follow the steps, you get a consistent result

2. Chaotic Systems

These are unpredictable and unstable

- There’s no clear order

- Everything feels random, and it’s hard to make sense of what’s happening

- Example: A natural disaster or sudden crisis – things happen fast and unexpectedly

3. Complex Systems

These are interconnected and constantly changing

- There’s no single cause and effect

- Patterns emerge over time, but they’re hard to predict

- Example: A community, the economy, or the climate – many parts interact, and small actions can have big ripple effects

What is systems thinking?

Systems thinking is a way of understanding and addressing complex problems by looking at the whole system rather than isolating individual parts.

It recognises that issues are interconnected, and that changes in one area can have ripple effects elsewhere. Rather than focusing solely on symptoms, systems thinking encourages us to identify root causes, map relationships, and understand feedback loops – helping us find leverage points for meaningful, long-term change. It’s especially useful in tackling complex challenges like poverty, climate change, or public health, where social, political, economic, and environmental factors all interact.

Practically Applying Systems Thinking

We can use systems thinking as a tool to solve complex problems. Practically, this means:

- Understanding the system we’re working in

- Understanding the places in a system where a small shift can lead to big improvements (‘leverage points of change’). This helps us identify where we should focus our energy and what interventions we should design

- Creating feedback loops to understand our impact, continually improving and experimenting

See our blog on how to create a strategy for systems change.

Example

Imagine you are the CEO of an organisation who works with prisoners to rehabilitate them back into society. You have tried many interventions; most have seen a small portion of prisoners rehabilitate successfully long-term, but many return to prison after a short period of time. You feel that your interventions are addressing surface-level issues, rather than root causes, and so are unsustainable.

You decide to take a systems change approach to your work. You:

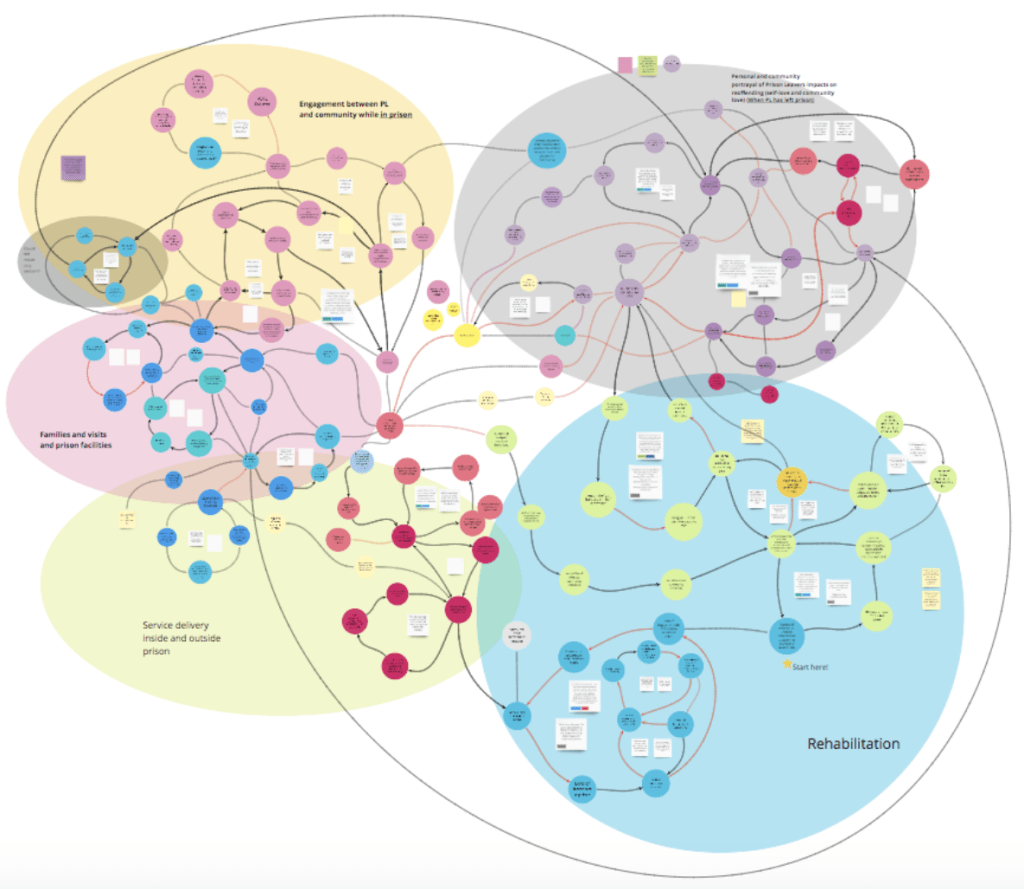

1. Begin by trying to understand the system you are working in. You define this as: the prison environment, and the socioeconomic environment prisoners find themselves in after release.

You begin by producing a visual systems map that identifies key actors (e.g., prison staff, probation officers, employers, families, social services), the relationships between them, and the underlying behavioural and cultural norms – such as stigma around criminal records, funding biases, or institutional distrust.

2. Identify leverage points for change. You conduct interviews, have informal conversations and ask those with lived-experience to produce a map of their history and experiences in the system. You do this with former prisoners, staff, and community partners.

You find that one major barrier is the lack of stable employment post-release. But deeper still, the stigma held by employers and systemic lack of coordination between prisons and job networks are key reinforcing loops. You realise that changing employer perceptions and embedding vocational training inside the prison system could be high-leverage actions.

3. Design interventions informed by the system. Rather than launching isolated job fairs or short-term skills programmes, you co-create a long-term strategy with multiple stakeholders: a mentorship programme connecting former prisoners with local business leaders, policy advocacy for fair hiring practices, and a pilot project embedding pre-release job placements within trusted employers.

4. Create feedback loops. You track not just how many people get jobs, but how well they reintegrate socially, their mental health outcomes, and employer retention rates. You build regular reflection sessions into the programme, enabling iteration and adaptation based on what’s working and what’s not.

source: https://medium.com/@myroslavazel/feedback-loops-in-system-thinking-7ef06e2ff310

Through this systems approach, you start to shift the conditions that lead to recidivism – not by fixing individuals, but by transforming the environment they return to and the assumptions that shape their opportunities.

Conclusion

Systems thinking doesn’t have to feel abstract or overwhelming. At its core, it’s about stepping back, seeing the bigger picture, and working with others to understand and shift the deeper conditions that hold problems in place. Whether you’re leading programmes, designing policy, or simply trying to create more lasting impact in your work – systems thinking can help you move from quick fixes to meaningful, sustainable change.

See our resources page for useful tools for each stage of this process!