By Maisie Jeffreys

When we talk about mental health, we often zoom in – on the individual, their symptoms, and what support they need to cope or recover. While this lens is important, it can also be limiting.

What if, instead of asking only “What’s wrong with you?”, we asked “What happened to you?”, “What surrounds you?”, and “What systems are you navigating every day?”

A growing number of voices – from activists and practitioners to researchers and those with lived experience – are calling for a shift in how we understand mental health. At the heart of this shift is systems thinking: a way of seeing not just isolated events, but the complex webs of causes, relationships, and feedback loops that shape our lives and wellbeing.

Because the truth is, mental health is never just personal. It is deeply political, social, and systemic.

Mental Health Doesn’t Happen in a Vacuum

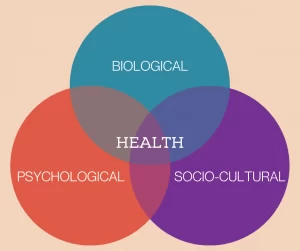

We know that mental health is shaped by much more than biology. It is influenced by issues such as housing insecurity, racial discrimination, financial stress, climate anxiety, precarious work, social disconnection, and countless other conditions that lie beyond the reach of therapy or medication alone.

For example:

- A young person experiencing anxiety may also be living in a neighbourhood with underfunded schools, police surveillance, and few green spaces

- A mother struggling with depression may be balancing caregiving, low-paid work, and navigating immigration systems

- A refugee experiencing trauma may also be facing language barriers, temporary housing, and restricted legal rights

If we treat mental health only at the individual level, without addressing these systemic stressors, we risk blaming people for struggling within systems that are designed in ways that harm them.

What a Systems Lens Reveals

Systems thinking asks us to step back and see these interconnections. It helps us:

- Map the relationships between social conditions and mental health outcomes

- Identify feedback loops – like how economic stress leads to poor mental health, which affects employability, which then worsens economic stress.

- Recognise structural causes – such as policy gaps, discrimination, or power imbalances – rather than focusing only on symptoms.

- Locate leverage points where a small change – like universal childcare or trauma-informed public services – could have wide-reaching effects

In short, systems thinking helps us ask:

What are the conditions that produce wellbeing, and how can we design for those—not just treat their absence?

source: https://www.pmhacci.com/what-causes-mental-illness/

Designing for Collective Mental Health

To truly support mental health at scale, we need to stop siloing it. That means:

- In education: embedding wellbeing into school design, teacher training, and curriculum, not just adding a mindfulness app

- In housing: recognising how overcrowding, instability, and unsafe environments impact psychological safety

- In workplaces: going beyond resilience workshops to look at workloads, leadership, pay equity, and organisational culture.

- In climate action: understanding the mental health impacts of environmental degradation and ecological grief, and building collective spaces for meaning-making and healing

We must also question whose voices shape these interventions. Are we co-designing with people who live the realities we’re trying to change? Or are we applying technical solutions to moral and relational problems?

The Risk of Technocratic Thinking

Ironically, even systems thinking can become too technical if not grounded in real lives and lived expertise. Systems maps drawn in boardrooms or research centres risk becoming abstractions that hide power and pain.

To truly understand mental health systemically, we must centre those who are marginalised by the system – not just as subjects of data, but as designers, storytellers, and leaders in shaping new approaches. This aligns closely with decolonising mental health: challenging who holds knowledge, who defines wellbeing, and who has the power to intervene.

From Treatment to Transformation

The call here is not to abandon clinical approaches – they have value, especially when community-centred and culturally responsive. But if we truly care about mental health, we must go beyond treatment and toward transformation.

We need to invest in the social, cultural, and environmental conditions that nurture resilience, belonging, and dignity. That means policies that redistribute power. It means cities and schools designed for connection. It means funding models that support long-term, community-led mental health initiatives, not just crisis response.

And it means listening more – to young people, racialised communities, frontline workers, indigenous leaders, and those who’ve been let down by the system too many times.

Final Thought

Mental health is not a silo: it’s a mirror. It reflects how we care for each other, how we structure our societies, and what we choose to prioritise. If we want a mentally healthier world, we need to stop treating mental health as an individual issue – and start redesigning the systems around us with compassion, justice, and interconnection at their core.