By Maisie Jeffreys

We’re all no stranger to the unrealistic beauty standards perpetuated by societies today. We’re expected to nip and tuck, never age, never rest, and never quite feel like we’re enough. These ideals aren’t just unattainable – they’re exhausting. They reduce our worth to appearances, commodify our insecurities, and distract us from celebrating the fullness of who we are. It’s time we challenged the systems that profit from our self-doubt and instead embraced authenticity, diversity, and radical self-acceptance.

An Alarming Trend

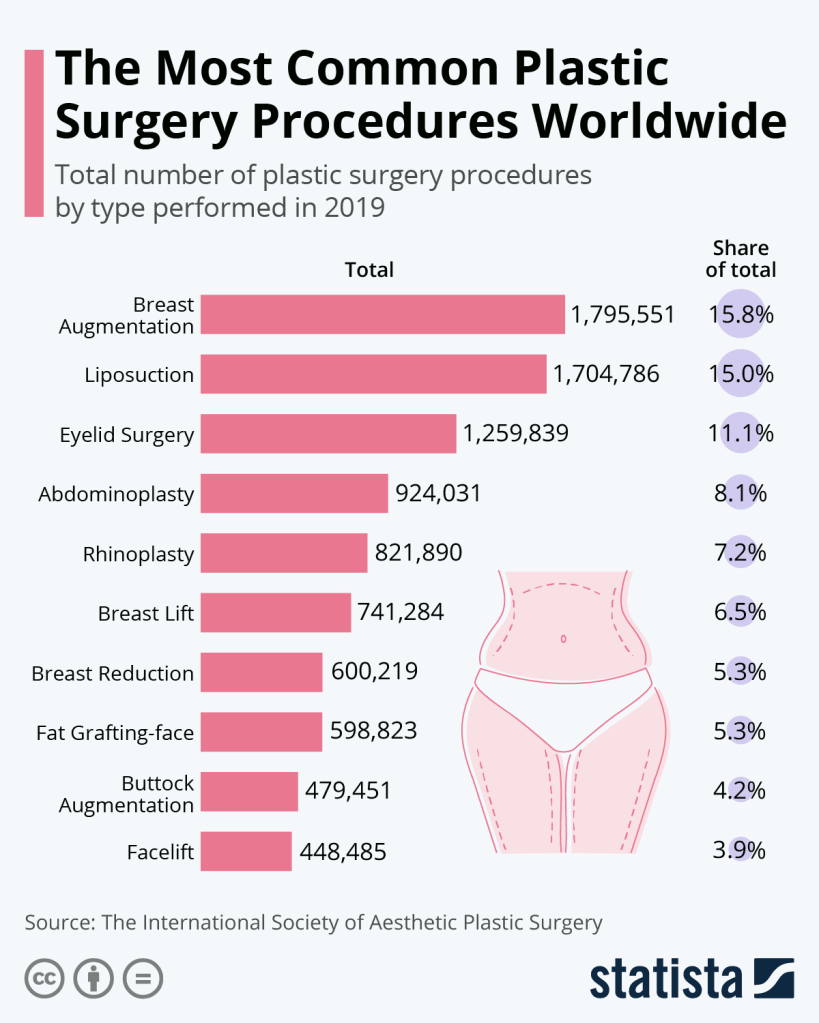

The number of individuals choosing to get plastic surgery is rapidly increasing – rising by 40% to nearly 35 million procedures from 2019 to 2023. A steady growth even amidst many countries facing economic uncertainty.

source: https://www.statista.com/chart/25322/plastic-surgery-procedures-by-type/

This could arguably be labelled as horrific: electing to undergo potentially painful, dangerous and life-threatening procedures by a largely unregulated global industry motivated by profit and not the welfare of people.

Understanding from a Systems Lens

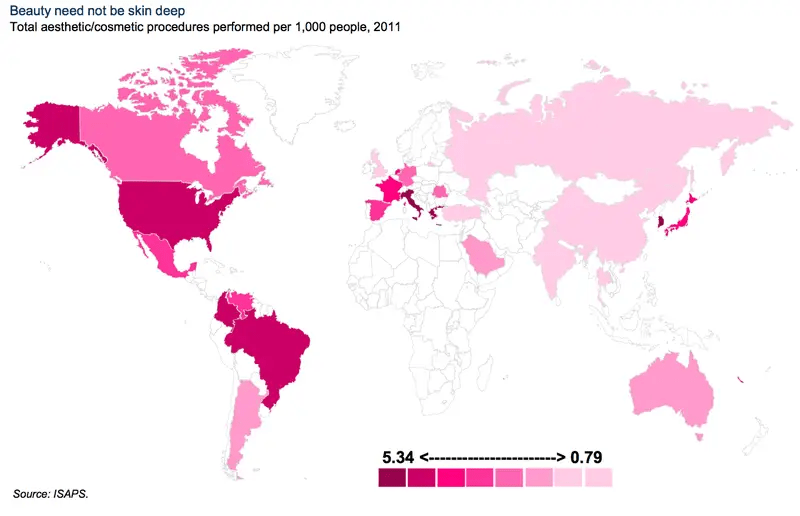

It’s easy to say that people who get plastic surgery are just ‘insecure’ or ‘vein’. However, plastic surgery becoming so commonplace is due to a complex interplay of socioeconomic, cultural and context-specific reasons that can vary across countries and regions.

source: https://www.businessinsider.com/map-of-countries-with-most-cosmetic-procedures-2013-12

If we take a systems approach, we can begin to understand that individual choices don’t happen in a vacuum. They are shaped by reinforcing feedback loops: media narratives that glorify certain body types, economic systems that commodify beauty, gendered and racial expectations tied to worth and value, and global industries that exploit aspiration and insecurity. These forces interact over time, normalising what once felt extreme and making the unnatural appear necessary.

“Here’s an unarguable truth: We like good-looking people more than bad-looking people. I am not going to discuss whether or not this is good. It’s a moot point. The evidence is overwhelming. Mothers give better care to good-looking babies. Teachers do a better job of teaching good-looking students, and good-looking people sell more (of anything) than less good-looking people.” – source: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/why-your-career-needs-plastic-surgery-literally/

From this lens, the rise in cosmetic procedures is not just a personal issue – it’s a systemic reflection of how power, profit, and cultural norms that shape our sense of self and self-worth.

Designing Interventions for Systems Change

Mapping these feedback loops can help us identify areas where interventions by governments, individuals, organisations can support systemic change to address the rise in harmful, unnecessary plastic surgery (not all plastic surgery is bad!).

Legends: S – same direction; O – opposite direction; B – balancing loop; R – reinforcing loop

In the above example of feedback loops in South Korea, known as the ‘plastic surgery capital of the world’, Nguyen et al. (2014) noted that the a key leverage point for improving plastic surgery outcomes lies in the experience and training of surgeons, which directly affects surgical success rates. A systems analysis using Causal Loop Diagrams and Bayesian Belief Networks reveals that South Korea’s government-backed promotion of medical tourism and cosmetic surgery has significantly influenced public demand, fuelled by media and marketing that idealise beauty standards.

They also noted that, while cosmetic surgery may offer health and aesthetic benefits, its risks are often downplayed. They recommended that the government should take a more balanced role by educating citizens on potential side effects, setting clearer boundaries for who cosmetic procedures are intended for, and implementing policies to screen and support candidates. Countries like Australia serve as examples, promoting body positivity and raising awareness of the risks.

One could argue that these recommendations still don’t address the root causes of escalating trends in plastic surgery – which lie with societal values, racism, and institutional oppression. However, this practical example does highlight how systems models can guide policymakers to better anticipate long-term impacts and avoid unintended consequences in the cosmetic surgery sector.

Conclusion

In conclusion, applying systems models to the cosmetic surgery sector allows us to move beyond surface-level trends and understand the deeper dynamics driving demand, risk, and regulation. By mapping these interconnections, policymakers can make more informed, ethical, and proactive decisions – balancing economic interests with public health and wellbeing. In a field where perception often outweighs precaution, a systems lens offers a powerful tool to ensure that interventions are not only effective, but equitable and sustainable.

Leave a reply to The Beauty Lie and the Systems that Benefit When People Hate Their Bodies – A Systems Lens Cancel reply