By Maisie Jeffreys

Racism without racists

…Is the title of Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s renowned book on color-blind racism in contemporary America.

It captures the idea that many white Americans today claim that “race is no longer an issue,” professing to be “color blind” whilst simultaneously denouncing those of colour for “playing the race card” or not “taking responsibility” for their own “race problem”. He points to the term “sincere fictions” to capture the systemic justification of racial inequality, and absolving of responsibility by white people – the notion that simply declaring “I’m not racist” means there is no problem ultimately perpetuates racism itself.

Indeed, race continues to shape life outcomes, and color-coded inequality persists:

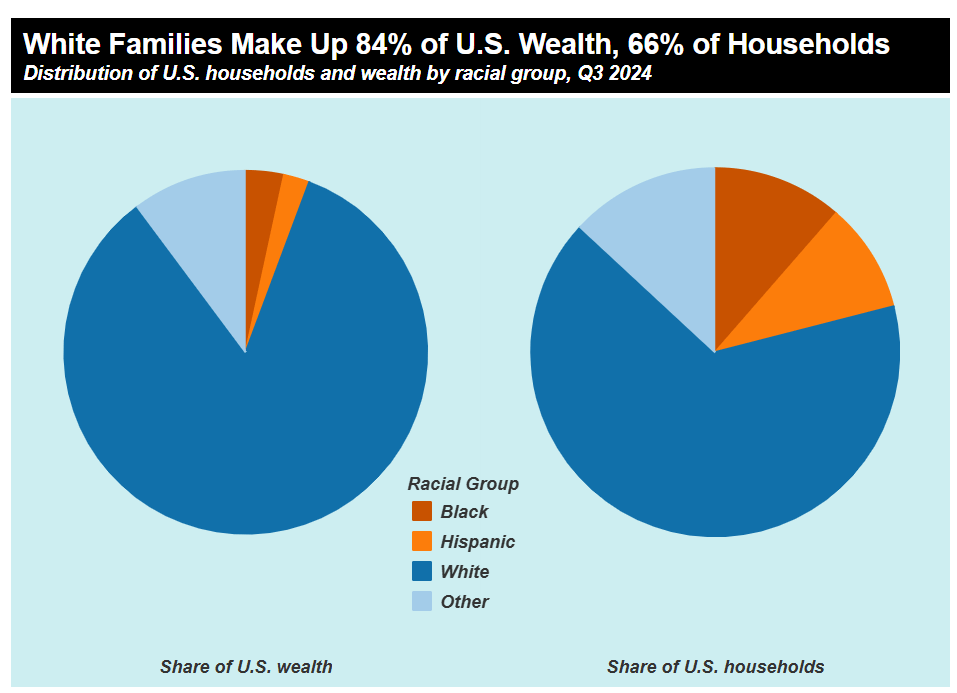

- White households hold 84.2% of all U.S. wealth while making up only 66% of households. This means white families hold about 15 times more wealth than Black and Latino families combined.

- The Black–white homeownership gap has grown from 26 percentage points in 1960 to 30 points in 2020.

- Indigenous people died from COVID-19 at a rate of 582 per 100,000, more than twice that of white or Asian Americans.

- The median net worth of white families is $282,310, compared to $44,100 for Black families and $62,120 for Latino families.

- Out of all Fortune 500 CEOs, only 4 are Black and 17 are Latino.

Source: US Federal Reserve

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

And the issue isn’t just limited to the US:

- In the UK, Black and minority ethnic (BME) people are 2.5 times more likely to be in poverty than white people. runnymedetrust.org

- Also in the UK: BME people are currently 2.2 times more likely to be in deep poverty compared to white people, and among specific groups (e.g. Bangladeshi people) it’s more than three times as likely. runnymedetrust.org

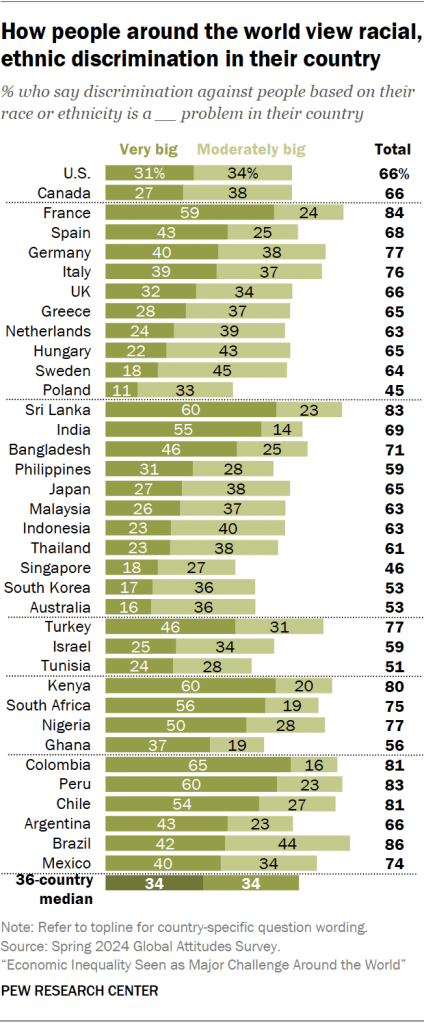

- Globally, more than half of people in many Latin American countries (Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru) believe racial or ethnic discrimination is a great deal contributing to economic inequality. Pew Research Center

- In France, research shows that racial minorities—especially people of Middle Eastern / North African (MENA) and Sub-Saharan African origin—face substantial earnings penalties, particularly around the median of the income distribution. WID – World Inequality Database

Source: Pew Research Center

A New Racial Ideology

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva coins a new racial ideology: color-blind racism. Unlike traditional racism, which attributes inequality to the supposed inferiority of people of color, color-blind racism allows white people to rationalise minorities’ social standing as the result of non-racial factors – such as naturally occurring phenomena, market dynamics, or cultural limitations – rather than acknowledging the role of systemic racial inequality.

For example, a white person may frame residential segregation as the outcome of natural group preferences – the idea that “certain groups just don’t mix,” and humans “naturally prefer familiarity”.

I definitely experienced this ideology when I worked in Madagascar. Several of my white colleagues were firm in their belief that Malagasy staff were not in leadership because they were “lazy”, working on “island time” and preferred to “nap during the day” – rather than the realities of institutional racism relegating highly-qualified, ambitious, non-white people to lower positions. When promoting a Malagasy colleague to a senior manager role, I even had him initially refuse because “those were white people jobs”.

A Systems Lens

Colour-blind racism may be the new racial ideology in parts of the world where the more “superficial”, or visible, elements of inequality have been tackled – for example, voting rights for those of colour or de-segregation of communal spaces. In these contexts, we may allow ourselves to turn a blind eye to the less visible elements that often remain unaddressed: the underlying mindsets, assumptions, and biases that continue to produce and sustain tangible inequalities. We can say to ourselves “we’ve done enough”, or “we don’t have a race problem in this country”.

This is further encapsulated in ‘System Justification Theory”. First proposed by psychologists John Jost and Mahzarin Banaji in 1994, the theory proposes that people are motivated (to varying extents) to defend, rationalise, and justify the existing social, economic and political systems – even when those systems work against themselves or others. This theory suggests that this tendency serves a psychologically comforting purpose by making people feel the system is fair, legitimate, and stable, thereby reducing uncertainty and anxiety. People may use the status quo as a reference point, and thus, any deviation from it may be perceived as a loss – even if advantageous. It can explain why people, including those who are disadvantaged, may resist social change and accept the status quo. This can be particularly relevant to tackling invisible drivers of oppression, that are often harder and more confronting for individuals to tackle.

If we were to take a systems-thinking approach and really look under the surface, we would see that color-blind racism is being used as a formidable tool in society, politics, economics, and beyond to marginalize people of color across the world. It is an ideology all too easy to fall into because it can falsely appear neutral, fair, and rational – allowing individuals and institutions to deny the existence of racial inequality while continuing to reproduce it through policies, practices, and cultural norms. In this way, color-blind racism quietly sustains systemic oppression, often without overtly racist actors even realising their role in it.

Credit: The Civic Canopy

Sexuality-Blind Homophobia, Gender-Blind Sexism

I would argue we can apply the principles of colour-blind racism to other forms of discrimination:

The concept of gender-blind sexism has been discussed in several forms of literature and extends Bonilla-Silva’s theory of color-blind racism to gender. In contemporary societies, women are often overtly treated as equals to men, yet outcomes often remain unequal due to subtle and covert forms of sexism and patriarchalism. Safeguarding the existing gender hierarchy requires active and “innovative” actions from men to reproduce their own power and dominance.

Similarly, sexuality-blind homophobia resists diversity in subtle, sometimes invisible – yet powerful – ways. For example, rather than outlawing marriage between non-cis, non-straight people, it is framed as “problematic” under the guise of protecting “family values.” Similarly, instead of imprisoning or punishing LGBTQIA+ people for being together, societal attitudes often insist that queer couples “keep it in the bedroom” and not “force” their sexuality on others – criticizing simple acts of affection like holding hands, kissing, or expressing love in public.

As a queer woman myself, I have many examples of the intersectionality between these two playing out in my life – particularly in my career. I remember when I became a senior leader of an organisation, and was told directly a male colleague – who themselves had no leadership experience – that “I’m not sexist, or homophobic, or anything – but I just don’t think you can do as good a job as the others.” I was happy to have proved him wrong.

Just as color-blind racism masks systemic racial inequality, gender-blind sexism and sexuality-blind homophobia obscure ongoing discrimination against women and LGBTQIA+ people, allowing subtle yet powerful forms of oppression to persist.

What Can We Do?

To challenge these forms of discrimination, we must look beyond surface-level equality and confront the underlying ideologies that justify inequality. This means recognising systemic bias, questioning narratives that blame marginalized groups for their circumstances, and actively creating policies, practices, and cultural norms that address the root causes of oppression. Only by acknowledging the invisible structures can we move toward genuine equity.

A Clarification

As Eduardo details in his book: the purpose of bringing to light colour-blind racism is not to demonize white people as a collective or individuals. I will reiterate this here, and similarly with regards to those who don’t fall into the categories of LGBTQIA+ or identify as women.

The point is not to assign personal blame, but to illuminate the ways that systemic inequalities are maintained through seemingly “neutral” beliefs and behaviors. By recognising these structures, individuals can understand their role within larger systems and take responsibility for how their actions, choices, and participation either perpetuate or challenge inequality, without conflating awareness with personal guilt.

Leave a reply to Is AI Creating Its Own Westernised, Global Knowledge System? – A Systems Lens Cancel reply