By Maisie Jeffreys

We treat body image like a personal problem – something we can fix through willpower, wellness, or self-love. But what if the problem isn’t individual at all? What if body hatred is exactly what capitalist, colonialist and racist systems needs to survive?

A History of Beauty

Beauty has long been considered one of the most enduring concepts – an ever-changing, fickle companion for humanity.

Even though “aesthetics” as formal branch of philosophy is a relatively modern concept, (developed in the 18th and 19th centuries), thinkers in Ancient Greece – like Plato and Aristotle – were already exploring questions about what makes things beautiful, how art affects people, and how beauty connects to goodness and truth. And it wasn’t always about looks.

In ancient times, art and beauty were seen as deeply tied to ethics and religion – moral and spiritual values were also a reflection of beauty.

Many indigenous cultures around the world also have a holistic notion of beauty intertwined with culture and wisdom. Adornments, beading, and body paint are not trends but intentional expressions of cultural identity, storytelling, community pride and opportunities for ancestral connection.

In the Navajo worldview (indigenous people of the Southwestern United States), beauty is integrated within health and harmony where, “Hózhó teaches first that beauty is one thing: everything.”

“Indigenous beauty to me is much deeper than the surface level. It starts from within; it’s the beauty in your mind and in your heart. Indigenous beauty is not just what you see; it’s how you feel. Beauty is in our creation stories, it’s in our ceremonies, it’s in our teachings, it’s in our relationships with the animals, the plants, and the land. The Indigenous view is that everything is interconnected, therefore, I believe that Indigenous beauty encompasses the beauty of everything that we see, feel, and experience. It encompasses our whole existence as human beings.” – Kendra Jessie aka Cedar Woman, 26-years-old, She/Her/Hers, Ukrainian/Cree (@kendrajessie). Source: Very Good Light

Of course, the concept of physical attractiveness has long existed – “Kalos kagathos” is a classical Greek phrase meaning beautiful and good – describing an ideal of personal conduct that harmonizes physical and mental excellence.

The idea of physical beauty being an indicator of goodness is one that solidified in the 15th Century with the rise of Christianity. Fair skin and hair, a youthful and virginal appearance were considered to be indicators of “God’s Light”.

Through colonialism, Christian ideologies of whiteness as a measure of worth, beauty and goodness were enforced on many areas of the world – touting anti-blackness and isolating minorities, especially those of colour. Stemming from Europe’s need to tightly control resources in times of scarcity, this was coupled with narratives of thinness and bodily restraint equating to “civilization”, whilst larger bodies and celebrations of abundance – particularly the cultural, communal celebrations of Indigenous and African societies – were labelled as “gluttonous” and “ungodly”. Colonial control over people’s bodies, land and minds became a tool of power.

[I talk about Christianity because it was a key theology used to justify colonialism and its ideologies. But, off course, it’s not just Christianity – many belief systems, political movements, and cultural narratives have been used throughout history to legitimise hierarchy, control, and exclusion.]

This binary worldview: fat vs thin, white vs black, moral vs immoral, was – and still is – a necessary foundation for colonial, racist and patriarchal systems to thrive. It enables those with power to reduce complex, dynamic human experiences to two sides of the same coin – creating one, Eurocentric framework for “good” and “beautiful”, and punishing those who do not conform.

It is these systems that constantly pit us against our peers, our “opposites” and ourselves. Even when we try to rebel, to ‘love ourselves’, the system sells us another version of self-optimisation. The language changes, but the underlying message stays the same: you are the project, and you are never done.

The Systems Behind The Mirror

Definition. Capitalism. Noun. An economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit. – Oxford Dictionary

Constantly changing our bodies and beauty has become a huge source of profit globally:

- The global weight loss industry was valued at approximately USD 296.8 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to USD 572.4 billion by 2033

- Worldwide beauty and personal care industry is worth approximately USD 646.20 billion in 2025 with forecasts expecting the market to reach over USD 1.15 trillion by 2034

- The global cosmetic surgery and procedure market size was estimated at USD 83.07 billion in 2024 and is expected to reach USD 195.87 billion by 2033

To keep us spending and consuming, these industries must convince us our bodies are the problem, and sell us the solution. You can see this in marketing campaigns, social media, television, magazines – it’s everywhere: lips too thin? Buy our plumping lipstick! Muscles too small? Here’s an exercise routine and steroids to fix that! Skin too dark? Whitening creams! Hooded eyes? Surgery! And the algorithms that drive what we see amplify idealized (often white, thin) bodies because insecurity drives engagement – and profit.

Just a simple google search for “ageing skin” comes up with countless results selling you products to “fix” this “horrendous” problem – with very few results that actually celebrate such beauty:

We’re so entrenched in the idea that beautiful = good that even in our workplaces, which supposedly should celebrate diversity, those who are conventionally attractive are more likely to get higher paid jobs, promotions, and better evaluations. Political candidates are more likely to get elected if they are deemed physically comforting. Dating apps create environments where physical attractiveness becomes the primary currency – the basis on which connection, attention, and even self-worth are negotiated. The pressure to conform is immense.

Just 4 of the Bond villains portrayed with facial disfigurements – a stark symbol in our media of beautiful = good.

Particularly with the rise of the plastic surgery industry and normalization of cosmetic procedures, appearance is no longer seen as a matter of genetics or individuality, but as a moral obligation – it has become a natural or ethical standard to fit into the current idea of “beauty”. Afterall, you can change anything for the right price…

I, for one, am sick of being told I need “fixing”, and that what needs “fixing” changes every month depending on what is most profitable. I am heartbroken that uniquely beautiful people feel so much pressure to conform that they pay extortionate amounts of money for products, take drugs, or even undergo painful procedures, to become “acceptable”.

I don’t see beauty in these industries. I see the systematic erasure of identity, individuality and heritage. I see the forced consumption, justification, and even glorification of colonialist ideologies that perpetuate racism, sexism and tie a desirable appearance to worth.

Did We Ever Consent?

I’ve heard the argument that beauty standards are a part of natural selection – as biological animals, we are programmed to pick mates we find attractive.

Whilst natural selection does certainly influence the physical appearance of animals – for example, the bright feathers of a peacock or the symmetry of a bird’s plumage signaling health and fertility – human beauty standards go far beyond biology, functionality or survival. I would argue we consider “attractive” is not innate but constructed, changing across time and context.

Naomi Wolf talks about this in her book, The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. “There is no legitimate historical or biological justification for the beauty myth,” she writes, noting that anthropologists haven’t found proof of the theory that today’s ideals stemmed from the evolutionary process of mate selection. Dr. Hannah McCann, a cultural studies lecturer at the University of Melbourne, agrees: “To suggest that there are universal ideals of beauty that transcend culture … completely fails to comprehend the way that ideals of beauty have been constructed in order to be sold.”

I would go one step further here and argue we are subjects of engineered consent.

The term was coined by Edward Bernays – the “father of public relations” – who believed that mass opinion could be shaped by those in power by a) understanding the motives and physiological profile of the public b) attaching marketing to those attitudes. Building on Freud’s theories of human desire, Bernays argued that if you can control what people want, you can control what they do.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.” – Edward Bernays, Propaganda (1928)

At its core, engineered consent is about making people believe that their choices are freely made, when in fact those choices have been carefully constructed for them.

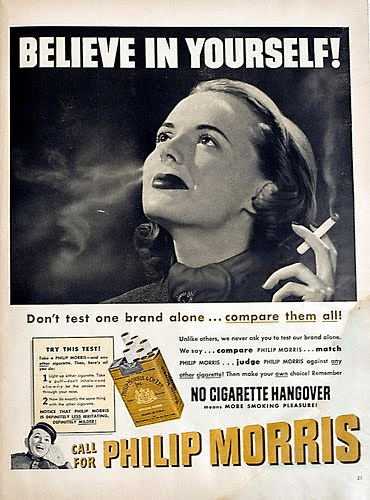

A great example of this is the tobacco industry. In the late 1920s, tobacco companies noticed that most smokers were men, and societal attitudes prevented women from smoking publicly orchestrated a campaign called Torches of Freedom, hiring women to smoke during New York’s Easter Parade as a statement of equality. The event reframed smoking as an act of emancipation, turning a social taboo into profitable marketing – and successfully doubled cigarette sales among women within a few years. Women believed they were independently choosing to smoke as an act of rebellion, when in fact they were being influenced to do so.

Source: https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/02/27/torches-of-freedom-women-and-smoking-propaganda/

This is exactly what the modern beauty industry does.

Advertising, algorithms, and influencers don’t just reflect what people desire – they manufacture those desires. Recognising the desire for “liberation” and “empowerment” among the public, beauty industries have attached their products to these concepts. We’re told we’re empowered to choose how we look, but the system defines the range of acceptable choices: thin, white, youthful, cisgender, able-bodied, and then sells you the method (product, surgery, drug, filter) to “choose” accordingly. Anything outside of that becomes “brave” at best or “undesirable” at worst. You think you’re choosing what you look like – but really you’re just choosing how you pay to get there.

As Waleed Tariq notes in his blog The Engineering of Consent, the process “is not about coercion, but the subtle creation of perceived freedom – the illusion that our decisions are our own.” When we buy into beauty culture, we’re exercising agency within a system that has already decided what agency should look like.

We scroll, we compare, we consume – and we call it self-expression. But this is systemic design. Consent has been commodified.

At What Cost?

Growing evidence highlights how unrealistic beauty standards affect individual meatal health – contributing to challenges such as eating disorders, body image dissatisfaction, body dysmorphia, anxiety, stress, isolation from peers, low self-esteem, and depression.

Source: Mental Health Foundation

For people of all genders, backgrounds and cultures these standards can serve as a constant barrier to true self-love and the acceptance of others. They make it acceptable to judge ourselves and others based on the colour of our skin, whiteness of our teeth, thinness of our legs… reinforcing systemic biases and perpetuating a narrow definition of beauty that excludes diversity and authenticity.

The Individual In the System

An important point of clarity here: we often speak of systems as if they are some intangible thing out of our reach and influence, something we can’t comprehend. But I want to stress that, at the heart of systems, are people.

People can be influenced, and systems can be changed. So I invite you to reflect:

- What level of responsibility or power do we have as individuals?

- What happens if we withdraw our participation?

- What happens if we question more?

- What would a system built on body respect – not control – look like?

Leave a comment